HARTWICK'S HISTORY

Founded in 1797 by John Christopher Hartwick, Hartwick is proud to be one of the oldest colleges in the country and the first Lutheran Seminary in the United States.

Chapter One: Who was John Christopher Hartwick?

Chapter Two: Hartwick Seminary (1797 – 1897)

Chapter Three: Seminary II (1898 – 1925)

Chapter Four: A Greater Hartwick and a Greater Oneonta (1926 – 1939)

Chapter Five: Hartwick’s War and Post-war Experience (1939 – 1958)

Chapter Six: Years of Change: 1960s Through 1990s

Chapter Seven: 2000 to the Present

An Education of Influence

A native of Germany, Johann Christoph Hartwig was born January 6, 1714, in the outskirts of the Gotha district (pictured). He was schooled in his hometown of Molschleben before advancing to the University of Jena in 1736, which was founded as a home for new religious ideas and continued as one of the more politically radical schools in Germany.

Documents show Hartwig (later Hartwick) matriculated at the University of Halle (pictured) in 1739. There he trained in theology and was influenced by the university’s status as a hub of German interest in American missionary and educational work. It was also a center for the Pietist school of Lutheran Christianity, which emphasized a guide for practical Christian living.

Among his faculty was Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, (pictured) a pietist who went on to become the father of American Lutheranism and Hartwick’s lifelong friend. After first teaching Latin in Halle, Hartwick was ordained in London in 1745 to become a pastor in America.

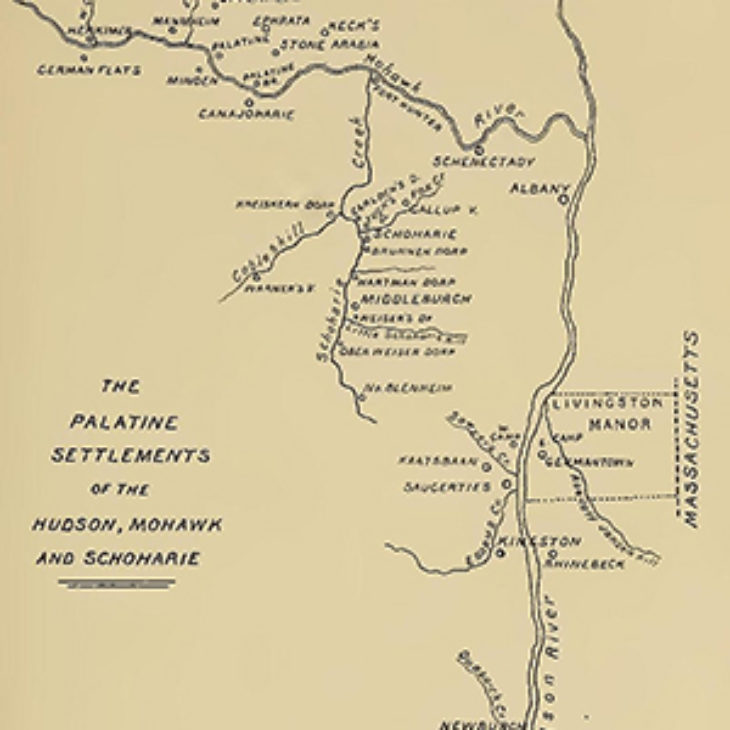

There he began his life’s work, serving the Palatines who had fled the French invasion of Germany and settled in the Hudson River Valley of New York and pursuing his vision for a New Jerusalem (pictured).

Life in America

When Hartwick arrived in America in 1746, he took responsibility for five congregations in the Central Hudson parish. These included Rhinebeck (pictured), where he reconnected with Muhlenberg. Photo courtesy of Historic Red Hook

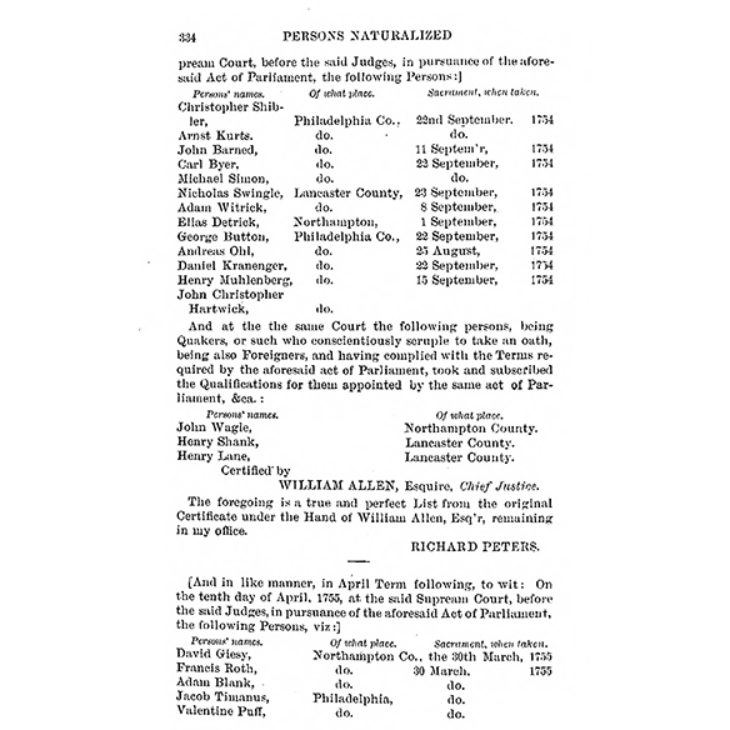

Hartwick and Muhlenberg attended the founding of the first Lutheran governing council in North America. Together, they also took the oath in Philadelphia to become naturalized citizens of Great Britain (see photo of naturalization book).

Hartwick was a man of high ideals and strong beliefs in the pietist interpretation of the Lutheran dogma. In one of his first interactions in America, he angered a prominent Lutheran leader of the old-line orthodox sect, Wilhelm Christoph Berkenmeyer. Hartwick’s beliefs and his association with Muhlenberg led Berkenmeyer to publish a tract against Hartwick, falsely accusing him of heresy. The accusations caused an uproar in one of his parishes where, according to Hartwick, he was attacked by Berkenmeyer’s followers “not only with words, but also with fists.”

Hartwick’s challenges continued with his difficulty adjusting to the pioneer life in America. He found the living conditions lacking and lamented having to travel long distances between parishes on horseback (pictured).

Despite these concerns, he declined opportunities to adopt a more settled life, and rarely stayed with any one church or in any one area for long. Records of his pastorates exist in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Maine.

When Hartwick tried to impose strict discipline among his parishioners, he often alienated them by making demands that were both unpopular and unrealistic. His colleagues complained “He is too austere in his manner and often does not speak to the people.” The historian for the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Frederick, Maryland, later described him as “a good and conscientious man, but his eccentricities sometimes interfered with his usefulness.”

A Man of Contrasts

At times described as rigid and unpolished, Hartwick was also known to be devout and learned. His book collection (pictured), much of which is now housed in the College’s Stevens-German Library, is a testament to the man’s knowledge of English, Latin, French, Greek, and Italian, in addition to his native German. Muhlenberg once said of his friend, “in a charitable spirit we saw through the faults which clung to him, to the excellent grounding in doctrine which he possessed.”

Hartwick’s strident beliefs and often inflexible approach could put him at odds with the very people he had come to serve. He was concerned about the “many opportunities here for temptation and willingness to sin” that he perceived among the new Americans.

History shows that the man at times held his parishioners to a different standard than he upheld himself. Despite his pietism – and the covenants Hartwick asked his parishioners to sign requiring that they forswear shooting, horse-racing, boozing, and dancing – Hartwick was not a prohibitionist himself. According to one biographer, “many old bills testify to the fact that he knew his liquor.”

Biographers also note Hartwick’s aversion to and avoidance of women; he is described as having been “fearful of matrimonial bondage, and shunned women as a plague.” Reverend Henry N. Pohlman, an early graduate of Hartwick Seminary and one of its trustees for many years, noted that Hartwick’s response to women was a subject of discussion among his contemporaries. “It was not an uncommon thing for (Hartwick), if he saw that he was about to meet a woman in the road, to cross over or even to leap a fence in order to avoid her.”

An Elusive Dream

Despite his difficulties, Hartwick remain steadfast in pursuit of his vision to create a New Jerusalem. He needed land for the venture and took steps to make purchases soon after arriving in America. His was to be a community of German Christians who would settle the patent and live in accordance with his beliefs and dictates. According to one biographer, “it would be wrong to conclude that he wanted to amass a fortune. He considered the land a trust from God, which he was to invest and return with usury.”

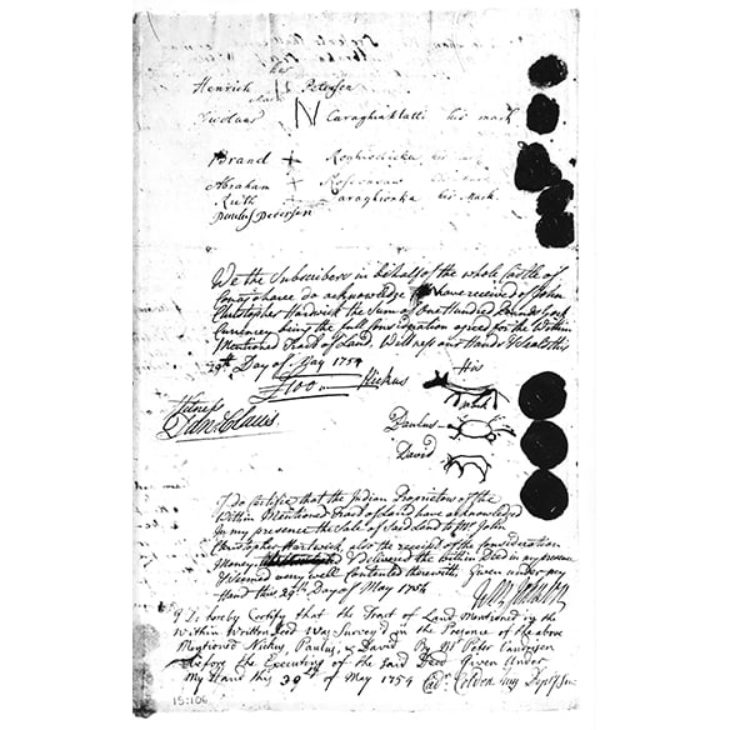

In 1750 Hartwick attempted to begin his colony by purchasing a 36-square mile parcel from Chief Hendrick Peterson (pictured), a prominent member of the Bear Clan and Speaker for the Mohawk Council.

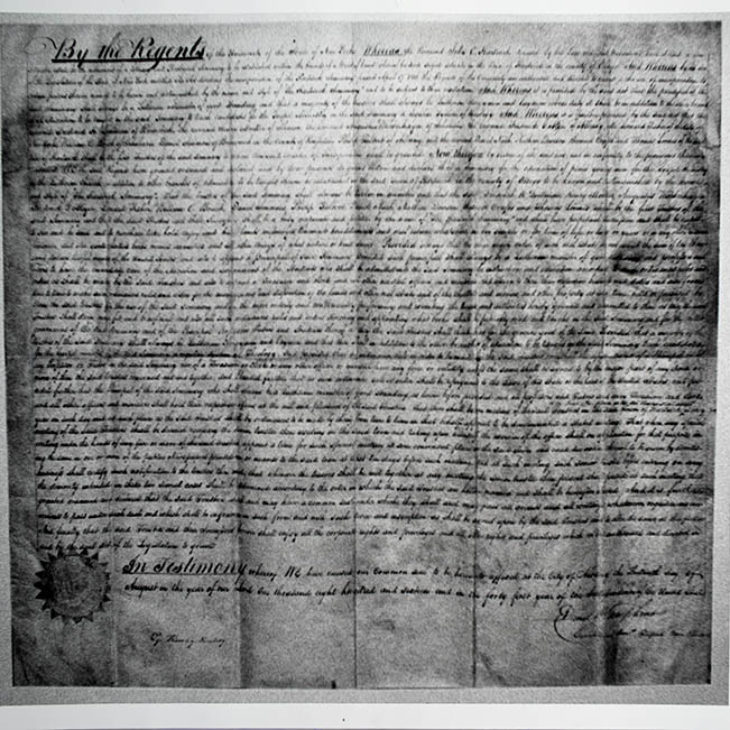

It would be 11 years before Hartwick was finally granted possession of about 16,000 acres (see pictured deed).

Circumstances thwarted Hartwick’s realization of his ideal. Challenges, including his frequent travels among parishes and his difficulties dealing with local land agent William Cooper, proved insurmountable. Settlers took little interest in his New Jerusalem – Hartwick’s strictures proved too burdensome for the new Americans, accustomed to the freedom and autonomy of frontier life.

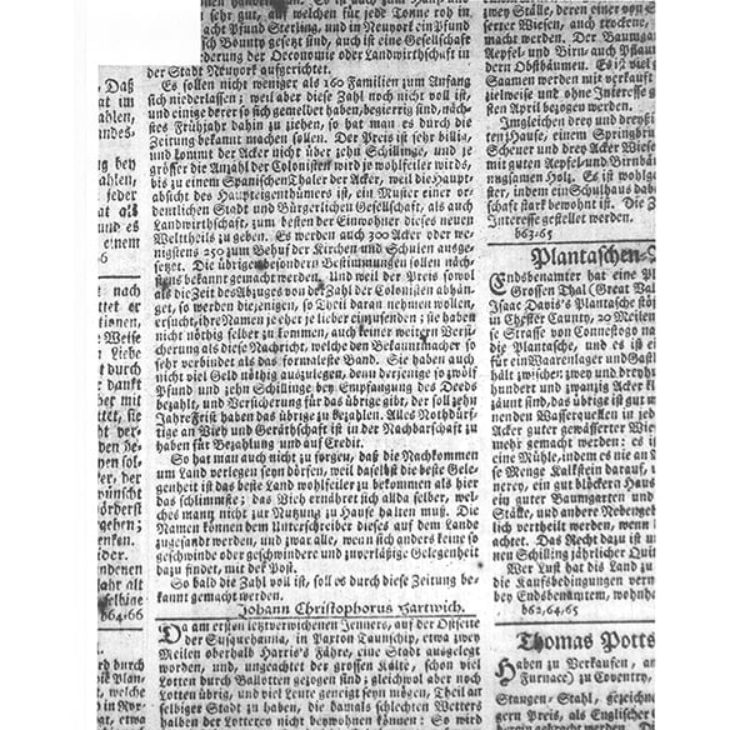

Still, the man remained determined. His efforts to enlist potential settlers ranged from inviting a ship of German prisoners to colonize the patent to placing newspaper advertisements to attract interest. One such ad placed in a Philadelphia German-language paper in 1765 described the advantages of the region, stating that “the Susquehannah River is… navigable for barges, bateaus, canoes and rafts and very convenient for the fur trade (pictured).”

By the mid-1780s, Hartwick was faced with a formidable competitor for the open countryside of New York. William Cooper (pictured) purchased a large tract of land through a foreclosure, moved to the region, and founded a village in his name. Soon he was offering land to settlers on terms far more attractive than those offered by Hartwick. Cooper also sold 3,000 acres of Hartwick’s land – a mistake he later tried to conceal – and began eyeing the unsettled Hartwick patent to the south. He first pressured Hartwick to sell, then purchased his mortgage and threatened to foreclose. In 1791, the aging Hartwick capitulated and gave Cooper power of attorney that enabled him to begin leasing the land, which Cooper did with no regard for Hartwick’s instructions. By the time Hartwick revoked Cooper’s power of attorney, the damage had been done.

Establishment of the Seminary

For five days in September of 1797, the executors of John Christopher Hartwick’s estate met in New York City, where they decided to establish a seminary in conformance with Hartwick’s wishes. The three executors were all highly influential men including Hartwick’s attorney, Jeremiah Van Rensselaer (pictured), who was Lieutenant Governor of New York and a member of Congress in the U.S. House of Representatives;

Frederick Muhlenberg (pictured), the son of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg and the first Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives;

and John Christopher Kunze, the foremost Lutheran scholar in America at that time (pictured). Kunze was named director, also per Hartwick’s instructions. The executors established a plan for teaching to begin right away out of Kunze’s New York City home.

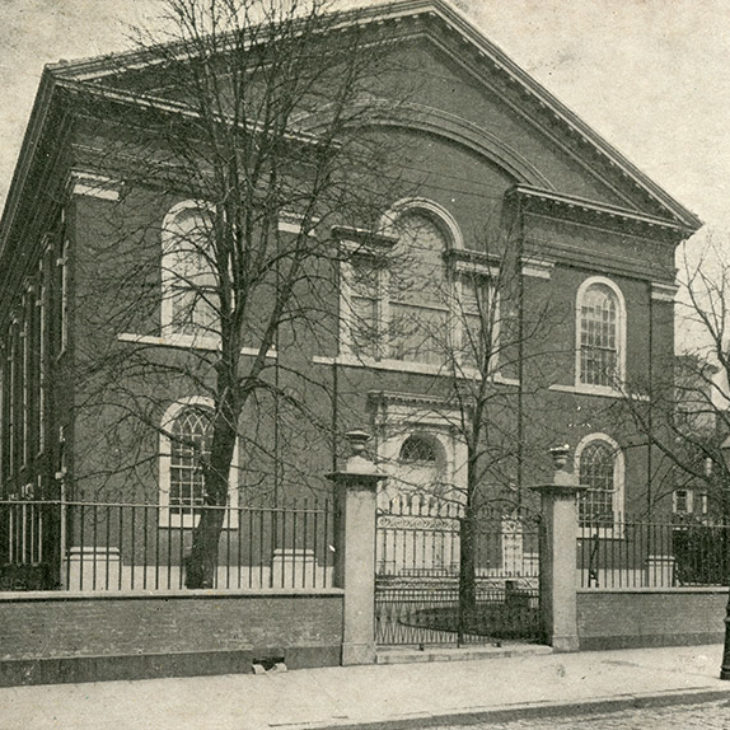

In 1803 Hartwick Seminary had its first graduate, Philip Frederick Mayer, who went on to have a distinguished career as pastor of the world’s first English Lutheran Church, St. John’s (pictured) in Philadelphia, for more than 50 years. Photo courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia

The estate executors still had to decide where to permanently build the seminary, and they considered several locations. William Cooper (pictured), the land agent who had undermined Hartwick’s dream of a New Jerusalem during his lifetime, wanted the Seminary to be located in Cooperstown, but Muhlenberg led the resistance to this idea. The members of Ebenezer Church, where Hartwick was once reportedly assaulted by an angry mob of parishioners, advocated to bring the Seminary to Albany. They offered $3,000 for a seminary building, a tempting offer in light of the fact that Hartwick’s estate, which had been valued at about $30,000, was much depleted by this time, a portion having gone to pay the debts of Muhlenberg who had died bankrupt.

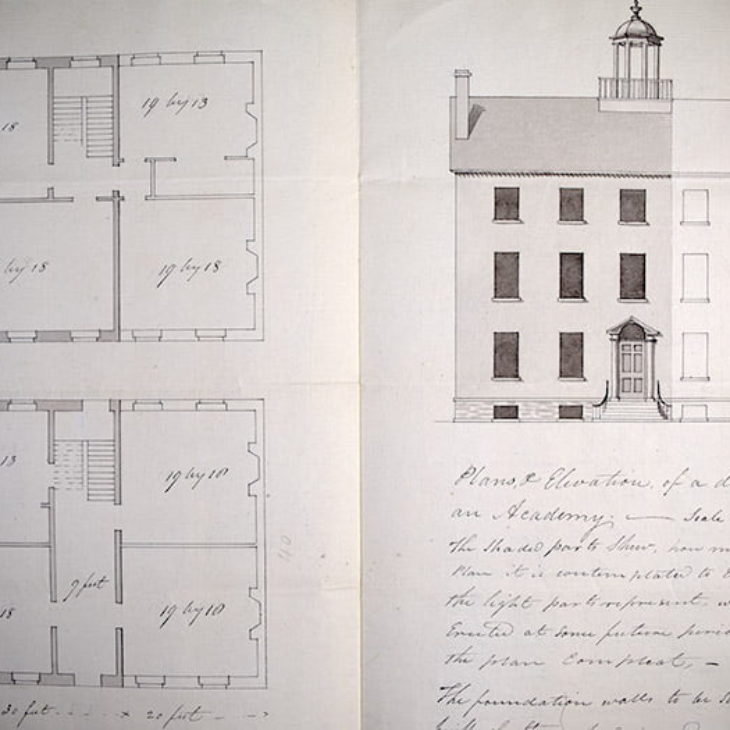

In 1804 construction began in Albany but legal troubles caused it to stall. Three years later Kunze died and in 1810 Van Renssaelaer, the last of Hartwick’s executors, also died leaving the remaining estate to the responsibility of his successor, Dr. John G. Knauff. Kuauff was a practicing physician in Albany and a trustee of Ebenezer church who has been described as the “unsung hero” of Hartwick College’s history. Knauff determined to establish the Seminary where Hartwick had intended—on his own patent. He solicited bids to construct a two-story brick building with 14 rooms (architect’s drawing pictured).

In 1815 construction was completed and Knauff hired the Seminary’s second principal and professor of theology, Ernest Lewis Hazelius (pictured).

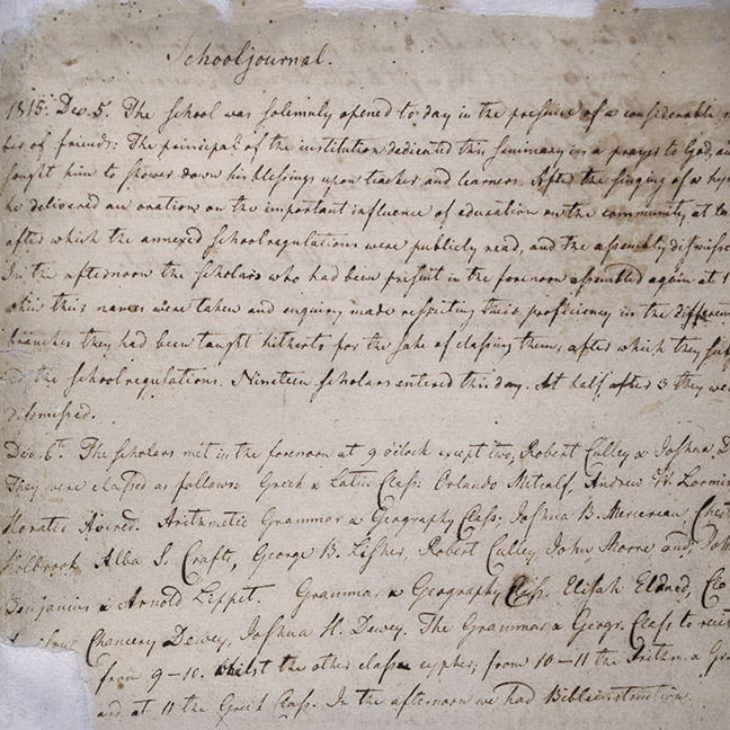

Hazelius began keeping a journal (pictured) including the names of students that is still displayed every year as part of Hartwick’s matriculation ceremony. Hazelius, born in the German part of Silesia, emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1801 after declining to join the Russian royal family through his mother’s connections to Catherine II, the Empress of Russia.

On December 15, 1815 the new bell (pictured)—commissioned by Knauf and today hanging in Yager Hall’s belfry—was rung and nineteen students attended class for the first time since Kunze’s passing eight years earlier. By the close of term, there were 44 students enrolled and the Seminary held its first formal commencement on August 26, 1816.

That year Hartwick Seminary was incorporated and a charter was granted by the Board of Regents (pictured). In September Knauff turned over the remainder of Hartwick’s estate – about $17,000 – to the Board of Trustees.

In addition to a theological school, Hartwick Seminary included a classical academy that functioned as today’s equivalent of a K-12 grade school. During its first three years there were no theological students, and throughout its existence the academy’s enrollment was generally much higher than the Seminary’s, peaking at 115 students, while the Seminary never enrolled more than 12 students at a time. Students as young as age seven commuted on foot or by horseback or wagon. Others boarded in the principal’s newly built 13-room house (pictured) or in neighboring homes at a cost of about $1.50 per week.

Hazelius was a dedicated leader who promoted extracurricular activities, served as the Seminary church’s pastor on Sundays, and performed missionary work during summer vacations, often bringing with him the divinity students. He was instrumental in gaining tuition-free admittance for the Seminary’s first and only identifiable Native American student of record. James Jimeson was a member of the Seneca Nation and he studied at the Seminary for four years before going on to medical school and becoming a surgeon in the US Navy. Hazelius also hired the first assistant teacher, John A. Quitman, son of the Seminary’s board president. Quitman Jr. left after two years to study law, and then to enter military and political life first as a major general during the Mexican War and then briefly as Governor of Mississippi. Quitman, an enslaver, is known for having played a significant role in the secession of the southern states before the Civil War. He was succeeded at Hartwick by Henry N. Pohlman (pictured), who in 1821 had been the first theological graduate of the newly established Seminary, and who went on to a long career as a Lutheran church leader and Seminary trustee. Enrollment and course subjects increased in the 1820s along with the proliferation of competing schools; students threatened to go elsewhere if they were not allowed to determine their own courses of study, and the Seminary bowed to their demands. At one point, Hazelius and his assistant were responsible for teaching a combined 41 courses in a single term, with enrollment numbering only 36 students.

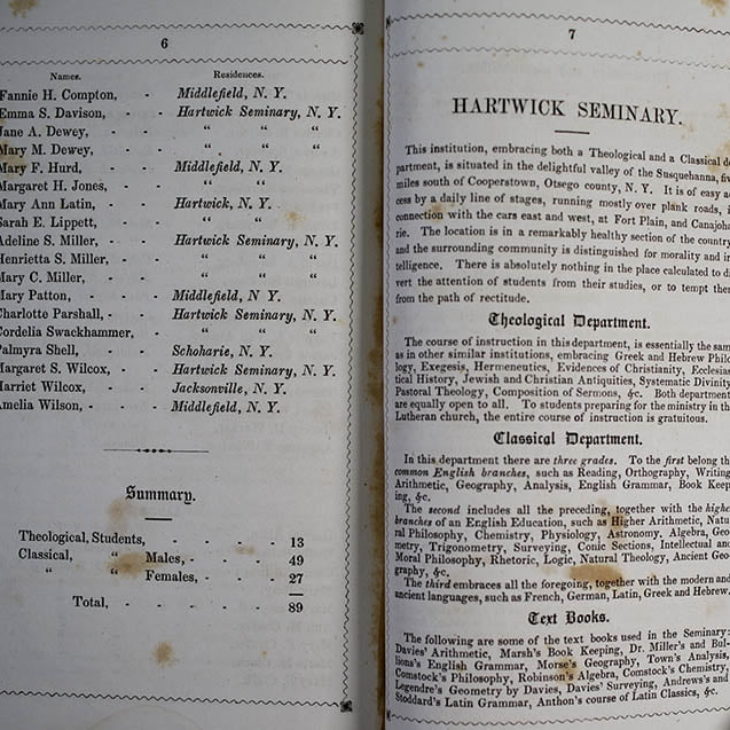

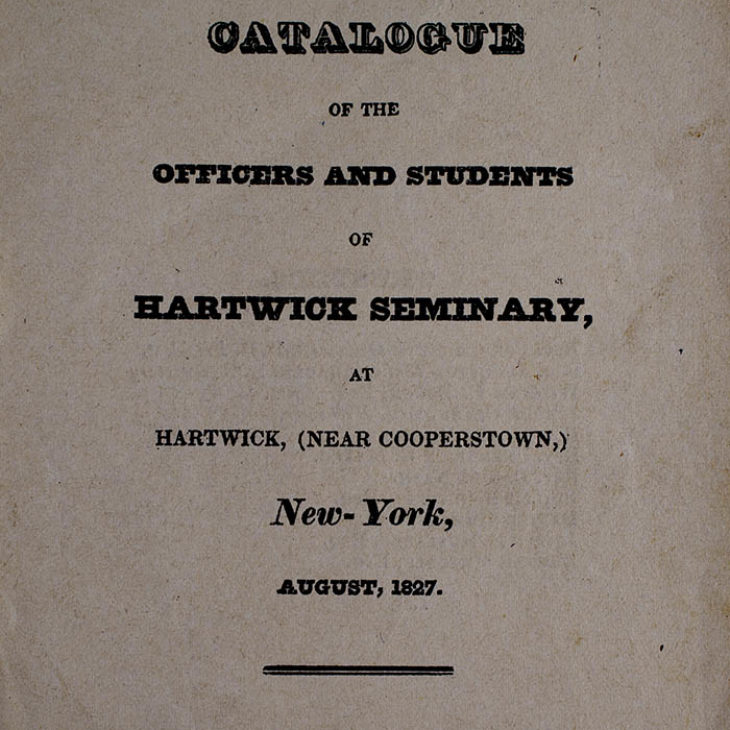

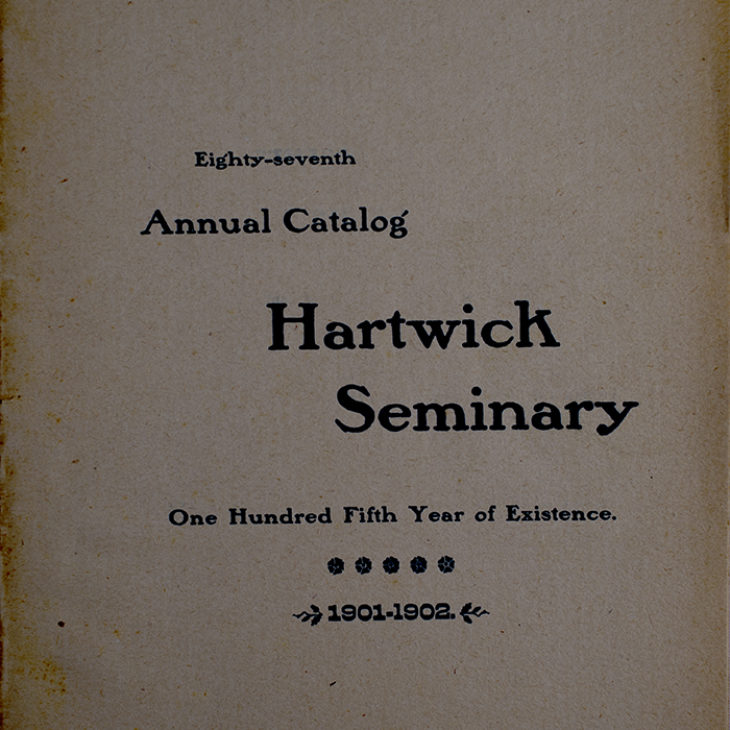

Tuition for each of the three 14-week terms was $4 with town residents receiving a discount and Seminary students attending tuition-free. Students studied English, grammar, arithmetic, geography, Latin, Greek, Hebrew and church history. (Catalog, pictured.)

Advanced course offerings included astronomy, physiology, agriculture, electricity, mechanics and civil engineering (Catalog, pictured.)

Life at the Seminary

Providing students with room and board was a group effort including the principal and his family, who lived in the Seminary building. With help from the students, the Travers split firewood, hauled coal, dispensed kerosene for the school and church lamps, harvested ice, grew vegetables for the Seminary tables, raised livestock, and did all the cooking. Principal Traver’s wife, known to the students as “Aunt Ettie,” and his mother-in-law, “Grandma Tompkins,” were in charge of the kitchen and dining room. The principal’s son Amos recalled his father undertaking any repairs he could do himself, as part of his frugal approach to the Seminary’s maintenance and operations.

The Seminary was shaped by its remoteness and rural setting; a 1901 school catalog described “surrounding scenery varied and picturesque” and a “climate entirely free from malaria.” It further asserted that “the institution is remote from the temptations and excitement of large towns and cities.” Seminary students were required to attend religious services daily, twice on Sunday. One student later recalled that she “must have heard the Bible read through at least once, probably two or three times.”

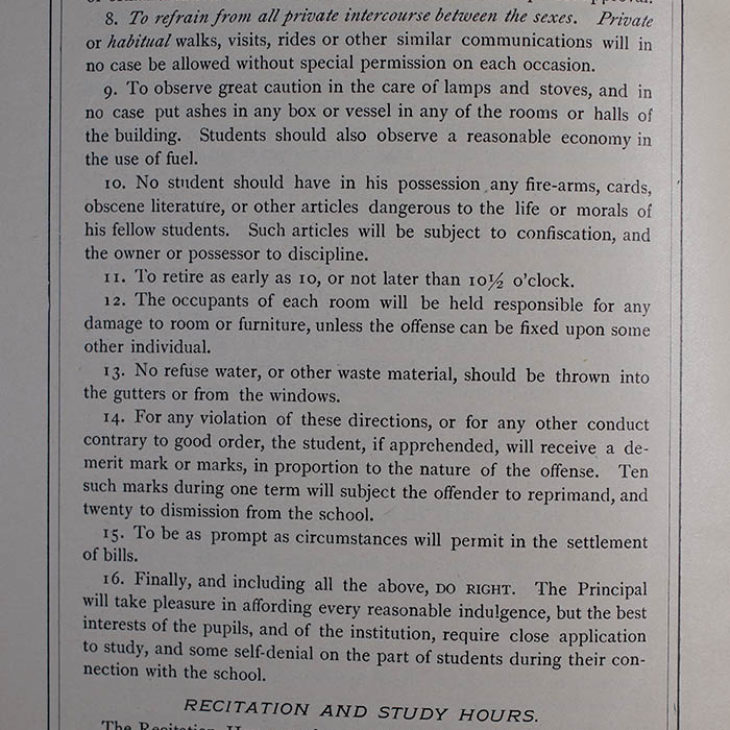

Student conduct was governed by an explicit list of rules, including No. 8, “To refrain from all private intercourse between the sexes;” as well as abstaining from profane or vulgar language and intoxicating liquors. Rule No. 16 admonished students to always “DO RIGHT,” noting that although students would be indulged to some extent, it was in their best interest to practice self-denial. There were also unwritten rules. In church, the male and female attendees always segregated themselves as a matter of practice, and young men were expected to wear a coat and tie to meals. As in John Christopher Hartwick’s time, dancing was still forbidden, although students routinely defied this rule and others, including the prohibition on smoking in rooms and the 10 p.m. curfew. The established gender roles of the time did allow conduct that would be strictly prohibited today – a female student dated her math teacher with the Seminary’s blessing, although the couple was carefully chaperoned.

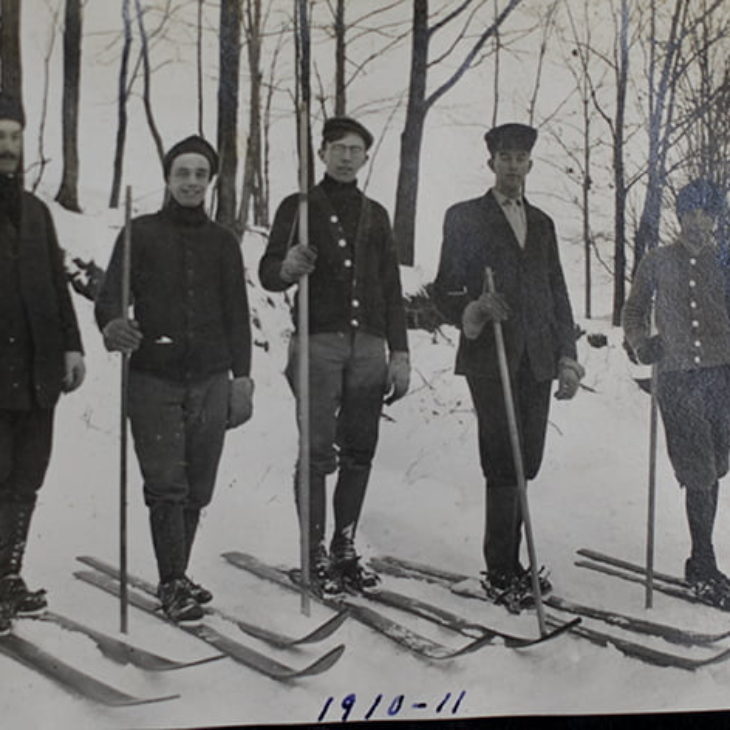

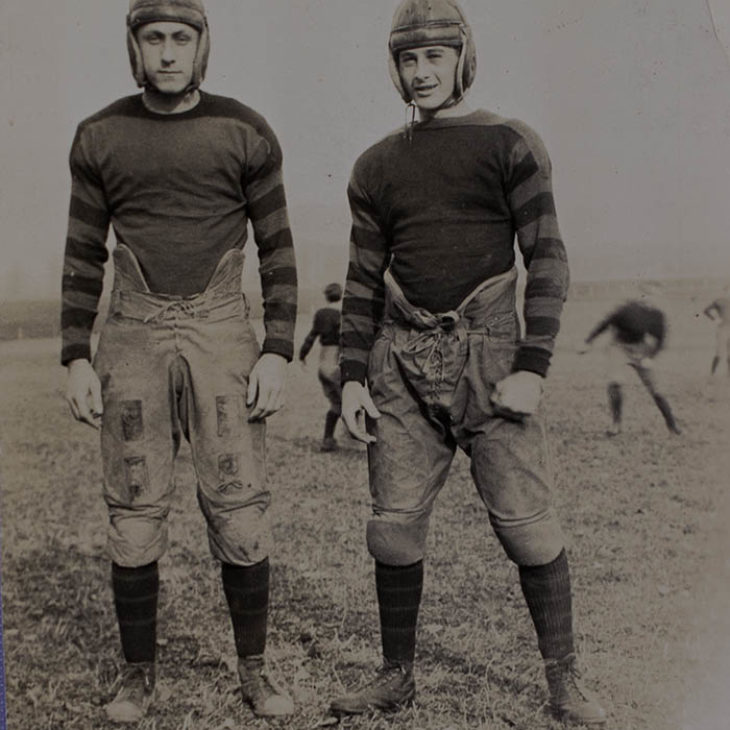

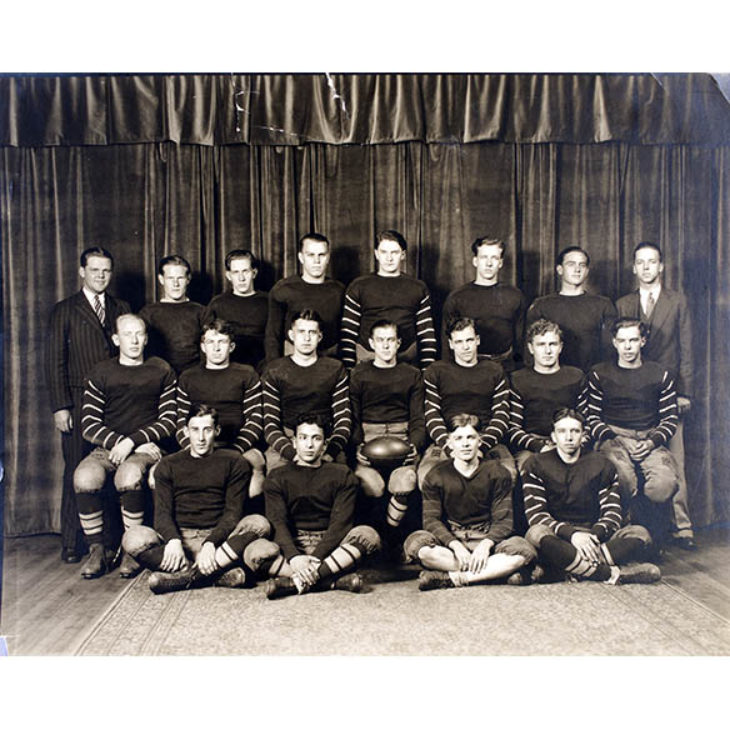

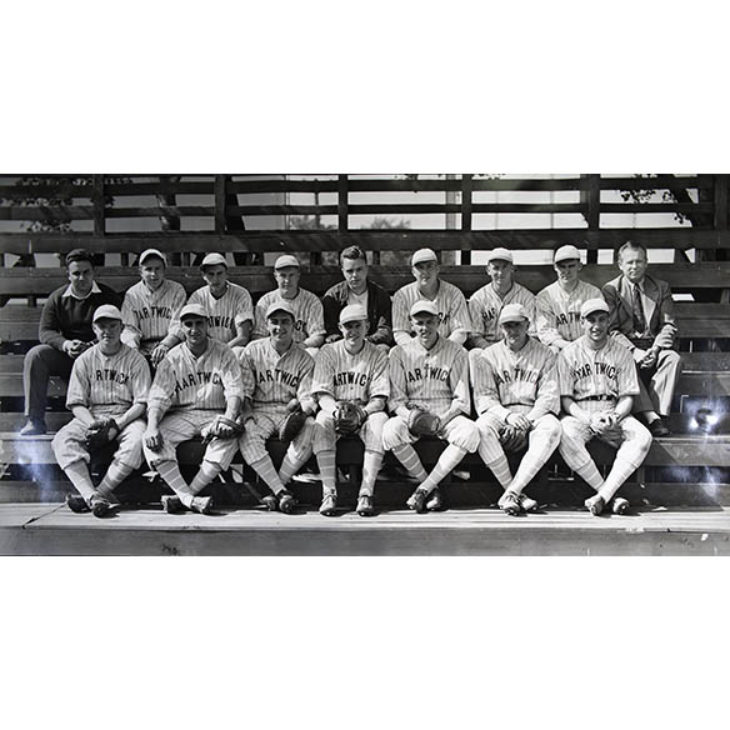

Despite all the rules, students found many opportunities for recreation and activity. They hunted, fished, skied and hiked, rode horses, made maple syrup, had tea parties, staged plays and debates, and went on strolls and outings with members of the opposite sex. Sports included boxing, baseball, and basketball. A football team formed in 1925 lost its first game, 83-0, against Cherry Valley, but later improved.

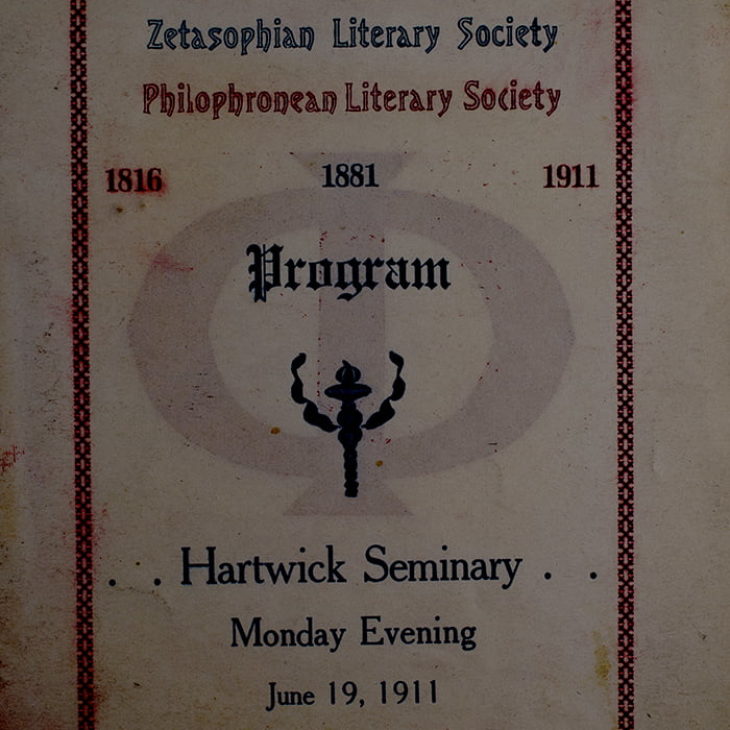

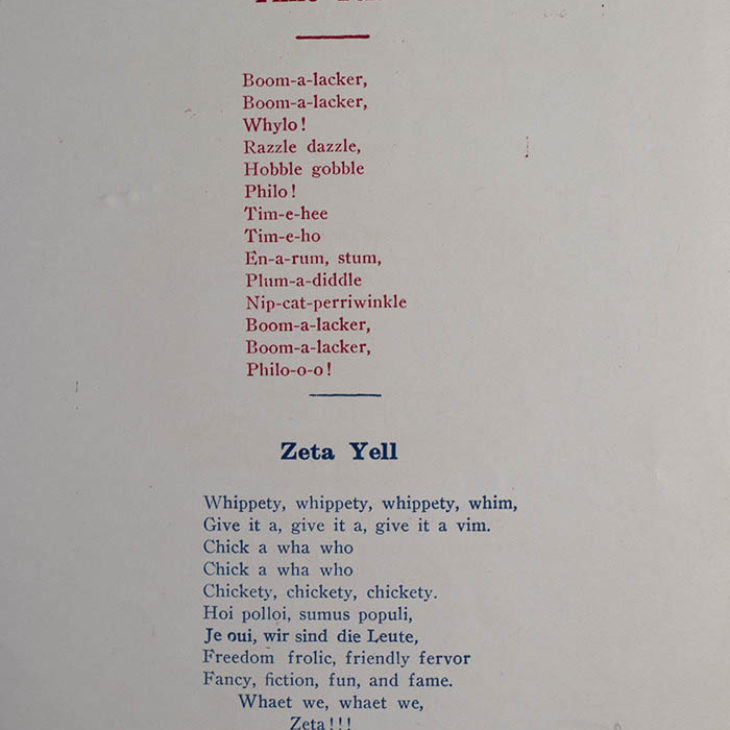

The debating societies for men (Philophroneans) and women (Zetasophians) remained an important source of social interaction and included debates between the sexes that were so heated they sometimes required staff intervention. Practical jokes were common and often involved livestock. Principal Traver once had to recover a pig after it awoke in the dormitory room where it was left unconscious as a prank. Older students would “baptize” newer ones by dropping bags full of water (or ink) on their heads from the Seminary tower.

In 1912 the Seminary received a gift from alumnus Andrew B. Yetter: a gymnasium, in which they hosted social events, plays, lectures, and men’s basketball games that were played initially by the light of kerosene lamps and a fireplace.

During the early twentieth century, several technological changes impacted the Seminary way of life. In 1915 a $20,000 renovation resulted in an indoor toilet, bath, and shower for men. A year later electricity was installed in the Seminary, which took some getting used to. The building was nearly destroyed by fire when students left maple syrup boiling down on six hot plates plugged into a single socket in their dormitory room. John Stolz, a student, noticed the black smoke coming into the hallway and broke down the door, putting out the fire with buckets of syrup. Principal Traver bought an automobile to replace his horse Fanny, who no longer had to pull wagonloads of laundry to be washed in Milford. As the number of automobiles on the road increased, hitchhiking became a common way for students to get to Cooperstown or Oneonta to see a movie on weekends.

The nineteen-teens were a fairly quiet period at the Seminary, despite the occurrence of World War I and the influenza epidemic of 1918, which caused the deaths of two students. Despite food and coal restrictions and some difficulties over the drafting of theological students, the war had little impact on the school. In 1919 Hartwick held its first Summer Assembly, a five-day event that was attended by 156 people who came to hear distinguished speakers including Dr. Anna Sarah Kugler, the first medical missionary of the Evangelical Lutheran General Synod of the United States.

Leadership Changes

During this period there were also changes to the administrative structure and oversight of the Seminary. In 1920, Dr. Alfred Hiller died suddenly after serving as head of the theological department for 38 years. That same year, Dr. John L. Kistler retired after 44 years’ service as a professor (37 of which he had also been the librarian) and Principal Traver stepped down from his leadership role. The trustees took the opportunity to create a new position of Seminary President, first held by Moritz G.L. Rietz, intended to be the public face of the institution. Hartwick Seminary had long maintained informal ties to the Lutheran church through its trustees, but in 1908 Seminary ownership had been transferred to the New York Synod with the hope that this would inspire greater support from the church.

In 1920 the synod undertook a campaign to raise $200,000 to increase the Seminary’s endowment and to finance construction of a library and girls’ dormitory building. The campaign raised enough money to purchase a nearby farmhouse and convert it into a girls’ residence—named Harroway Hall after the family whose $5,000 contribution enabled it. Throughout this period enrollment stayed at about 70 students total, including the four-year academy (similar to a high school curriculum), three-year theological school, and one-year collegiate program. For some time there had been talk of expanding to a four-year liberal arts college but plans did not come to fruition. These administrative changes, along with a controversial event that occurred in 1924, finally set the stage for the founding of Hartwick College.

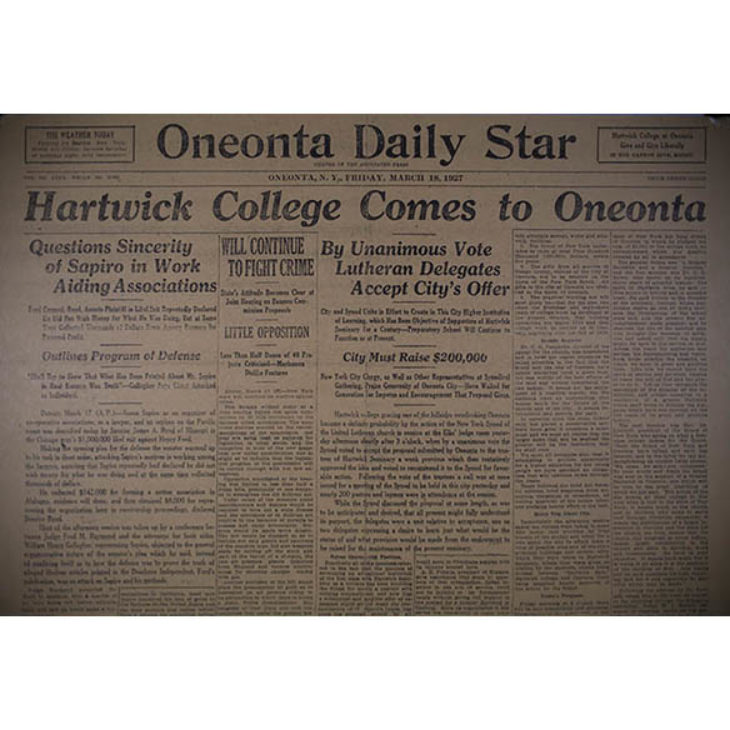

Hartwick College Comes to Oneonta

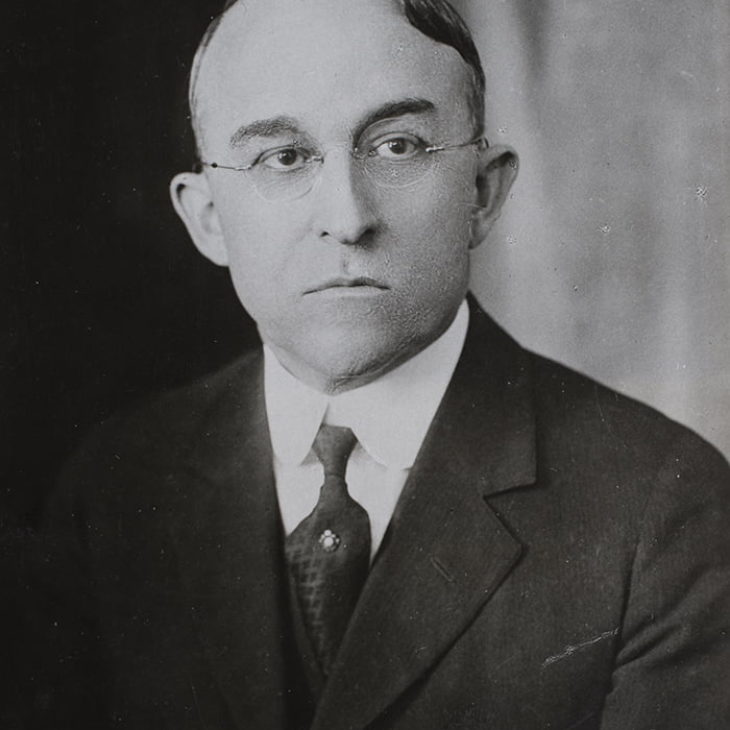

Hartwick Seminary president and principal Charles Myers was in 1926 the first to refer to “a Greater Hartwick,” although the idea of expanding Hartwick into a four-year college long predated his vision. Myers brought new determination to the effort, and that year he convinced the Board of Trustees to authorize a campaign to raise $500,000 for that purpose, among others. Initially the campaign seemed like it would go the way of several previous unsuccessful fundraising efforts. However, in March of 1927 Hartwick’s luck finally changed. The nearby city of Oneonta’s Chamber of Commerce made a proposal: if the Seminary would raise $400,000, the city would contribute $200,000 and provide land suitable for the present and future needs of an institution. Oneonta’s thriving business community welcomed the idea of being home to a four-year college. The seminary trustees voted quickly and unanimously to recommend acceptance of the proposal, and a week later the New York Synod delegates accepted it unanimously. According to Charles W. Leitzell who then served as president of both the Seminary board and synod, by building a new college in Oneonta “the old traditions will be given fertile soil in which to reach an even greater maturity and the sacred trust given by John Christopher Hartwick will not have failed.”

The backdrop for these developments was the enthusiasm and support shown by the citizens of Oneonta, who participated in large numbers in the meetings carried on between the city and Seminary representatives. Community members and local organizations quickly got involved, arranging lodging for the Seminary delegates in residents’ homes, and chauffeuring them around town to view possible sites for the new college.

By March of 1927 the new partnership and its campaign “A Greater Hartwick and a Greater Oneonta,” were underway. Fundraising began auspiciously with the first pledge made by State Supreme Court Justice Abraham L. Kellogg, followed by pledges from Sherman Fairchild (son of an IBM founder) and the Bresee family, totaling $25,000. The city’s door-to-door campaign, titled “Everybody Give Something,” began on March 24th and within 16 days had surpassed its $200,000 goal. Oneonta citizens donated what amounted to about $80 per family. The generosity shown by the community was even more remarkable in light of the fact that it contained very few members with any connection to Lutheranism. By early August the location was chosen and further donations in the form of land resulted in the 115-acre campus site known as College Hill. The following summer ground was broken for the first building, Science Hall, later renamed Bresee Hall in honor of charter trustee Frank Bresee.

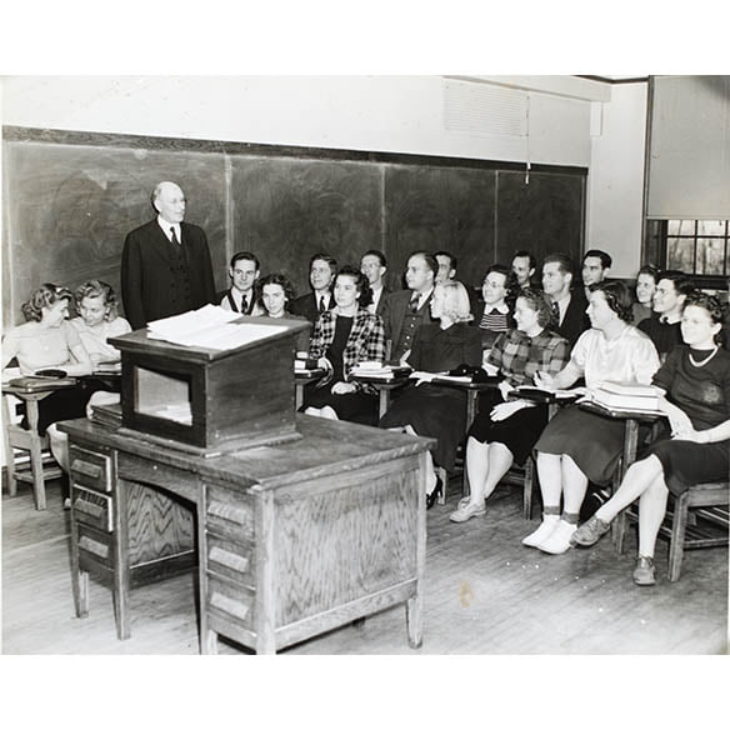

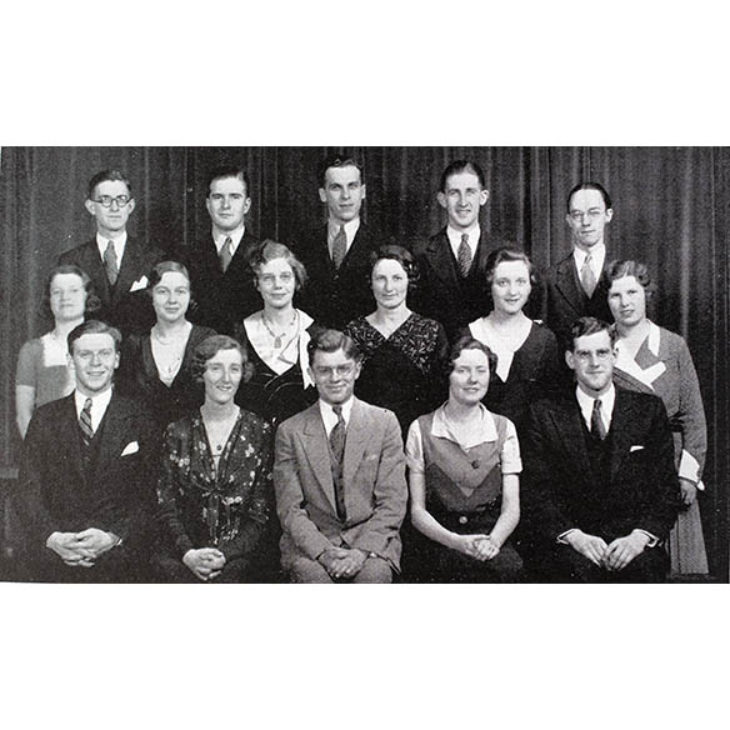

Charles Myers had been appointed president of the college, and he and the newly-appointed Dean Olaf Norlie were overwhelmed when 102 students enrolled. While construction of Science Hall was underway, the college opened and studies commenced on September 26, 1928 after an inaugural chapel service held at the Palace Theater in downtown Oneonta. Students walked down Main Street to the Walling Mansion, at the corner of Walling Avenue, where instruction would be held until Science Hall was ready.

Science Hall Completed

In 1929 Myers resigned and was succeeded by Charles Leitzell, the clergyman who had served as president of the Seminary board for more than 20 years and who was then president of the Hartwick College board. In December of that year, Science Hall was completed.

Although the campus architects originally envisioned it having seven buildings, six of them were never built.

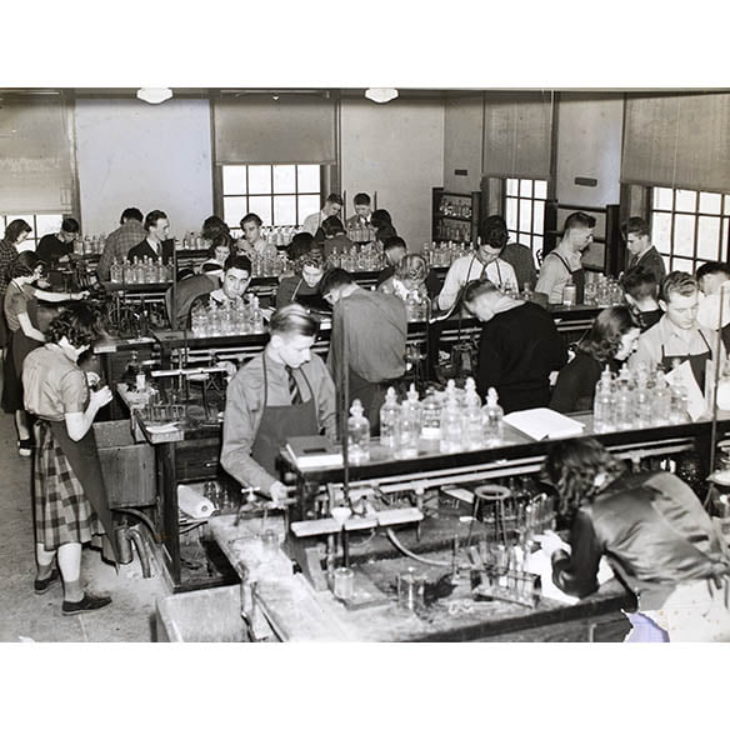

The timing of the new college’s arrival was not fortuitous—the stock market had crashed five weeks prior to Science Hall’s completion and the building became the entire campus: gymnasium, locker rooms, offices, chapel, library, women’s and men’s social halls, seven classrooms, laboratories, and faculty rooms. Notably absent were dormitories—students found accommodation in rooming houses in the community.

A New Institution

For such a small and new institution, Hartwick College offered a wide variety of courses, language courses in particular. In 1929 students were able to study Latin, Greek, German, French, Hebrew, Italian, Spanish, Scandinavian and Dutch. There was also an impressive array of extracurricular activites including a literary society, religious club, music club, concert band, violin quintet, chorus, dramatic group, and newspaper. Sports included basketball, baseball and football teams. However, the development of Christian character remained the chief aim and purpose of the new college. In addition to President Leitzell, eleven other charter trustees were Lutheran clergymen and Dean Norlie had a strict moral code that rivaled that of John Christopher Hartwick—he too forbade social dancing, as well as fraternities and sororities (although with President Leitzell’s blessing, three fraternities and three sororities began operating secretly). Students attended daily chapel services and the curriculum included 16 required credit hours in religion courses, a condition which at times met with organized resistance from students.

President Henry J. Arnold

Not long before the United States entered the Second World War, Henry J. Arnold became the first layman to head any Hartwick institution – Seminary, Academy, or College. He soon was tested to lead this college through a time of upheaval for the nation.

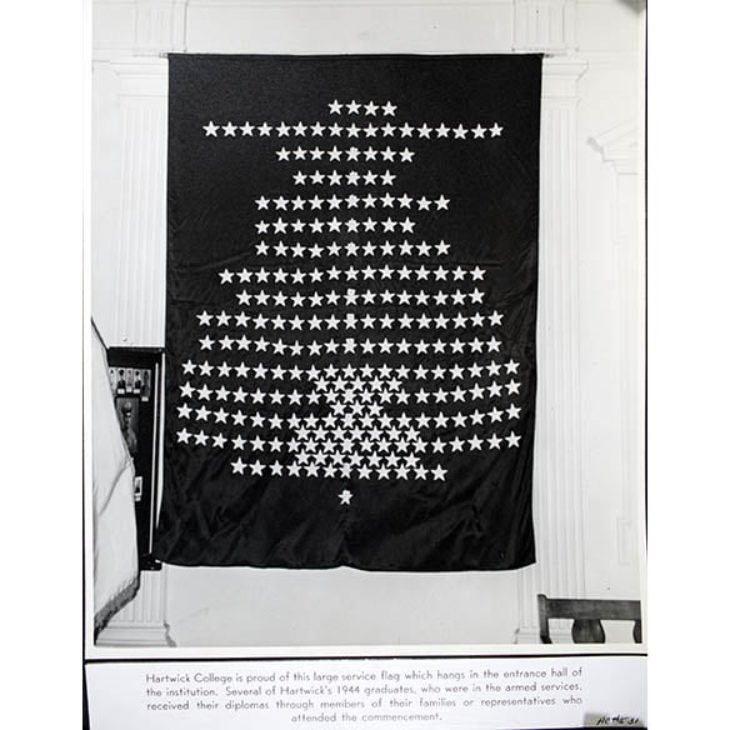

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, many Hartwick students enlisted or were drafted into the Armed Forces. The result: enrollments dropped by 40% and Hartwick faced a large financial deficit. By fall of 1943, enrollment hovered around just 100 students.

US Cadet Nurse Corps

Relief came in the form of a new program that has grown to become Hartwick’s largest major. In 1943, Hartwick was one of just a few colleges in New York State selected to train members of the new US Cadet Nurse Corps for duty in the Armed Services or public health.

Edith M. Lacey, an experienced and well-educated nurse, was named Dean of Hartwick’s new School of Nursing, leading 36 students through the three-year program of one year on campus and two years in clinical settings.

Part of the original Science Hall (now Bresee Hall) was converted into a nursing laboratory and nursing students resided in two College-owned houses on Clinton Street.

Minnie Marsh White Support

Another boost to the College came in 1945 with a generous bequest from Minnie Marsh White of Cooperstown, who gave Hartwick the resources it needed to get through the end World War II.

GI Bill of Rights

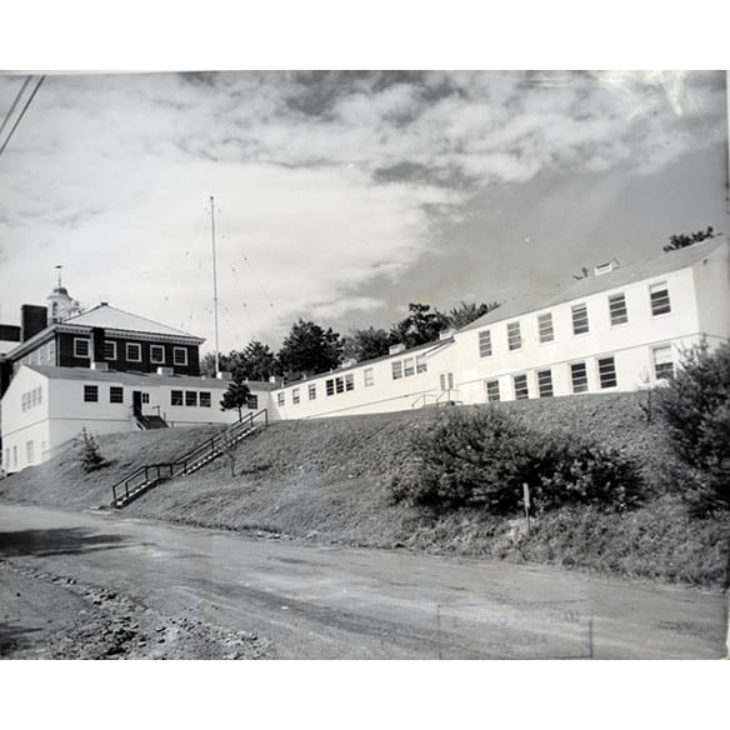

Growth followed the war when the GI Bill of Rights financed the education of many veterans. Hartwick’s enrollment tripled to more than 400 students by the Fall of 1946, invigorating the atmosphere on campus and bringing older, self-directed students. A critical shortage of infrastructure led to new buildings on campus—prefabricated surplus structures formerly used by the Army and Navy provided temporary quarters for 60 men and housing for married students, as well as needed classrooms and offices. One of these buildings was the first Leitzell Hall, a wood structure which burned down in 1958 and was replaced with a brick one. The new Arts Building looked so flimsy it was referred to as “Cardboard Alley,” a name which has endured through the College’s drama club.

After 22 years on Oyaron Hill, the College’s second permanent building was partially constructed in 1950 with the first wing housing the library. Initially known as the Religion and Arts Building, it was renamed after President Arnold. A south wing including a chapel was completed in 1953. New majors were created at this time, and the nursing program expanded from three to four years. Hartwick College earned its first accreditation from what is now known as the Middle States Commission on Higher Education.

President Miller A.F. Ritchie

The start of the Korean War combined with the decline in birth rates from the Depression caused enrollment to shrink again. Efforts at financial conservation and development included a new associates degree program, termination of the College’s football program, and a freeze on faculty salary increases. On the verge of bankruptcy, in 1951 the Bresee Family again came to the College’s rescue, pledging resources to keep it solvent at least temporarily.

In 1953, President Arnold retired and was succeeded by Miller A.F. Ritchie who inherited a $27,000 deficit and reportedly would not have accepted the job had he read the financial reports ahead of time.

Ritchie took decisive action to pay the College’s bills. He also implemented a new idea designed to not only increase its assets, but also improve relations with the city of Oneonta: Ritchie established the Citizens Board, a group of local businesspeople and civic leaders who would go on to serve for decades as a fundraising mechanism, sounding board, and advocate for the College.

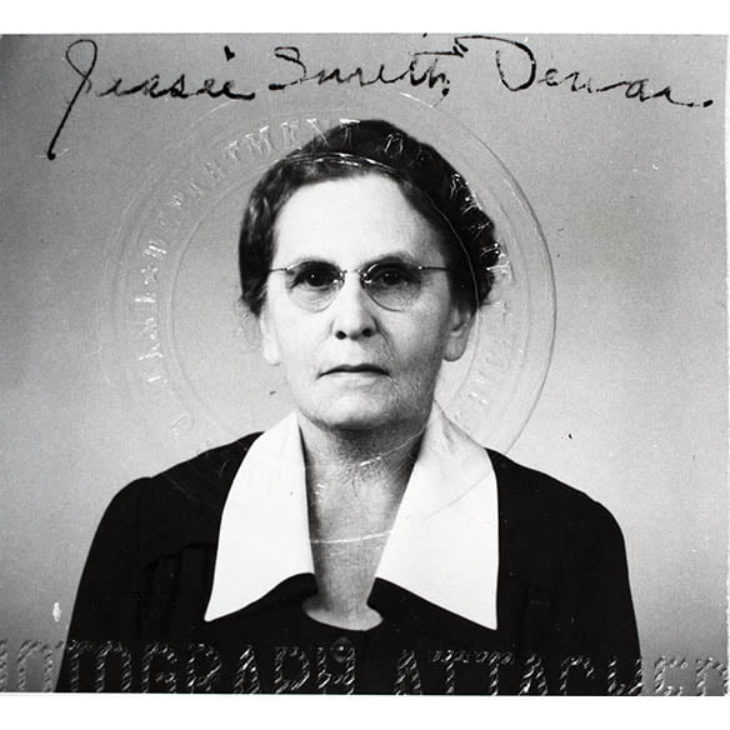

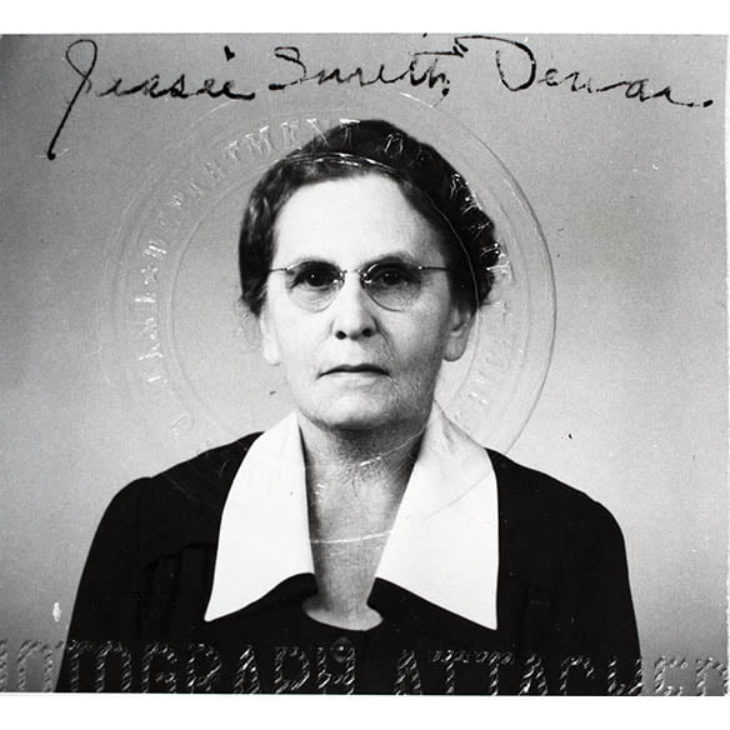

Ritchie, along with the College’s first director of public relations, H. Claude Hardy, successfully cultivated several relationships with community members that would bear fruit. Jessie Smith Dewar and the Dewar Foundation funded the first women’s dormitory on campus, including the first campus-wide dining room that served three meals a day and would become known as The Commons.

Marion Yager, sister of Willard Yager for whom Yager Hall is named, made a bequest of $1.7 million to the College.

1960s

The start of the 1960s saw Hartwick College on much firmer footing. Enrollment was above 500 and thanks to donors like Marion Yager, the endowment had reached $2 million.

The new decade began with a new president, Frederick Moore Binder, who was determined to strengthen Hartwick academically and grow the campus infrastructure. During his decade at Hartwick nine buildings were added as well as improvements made to existing ones. The Campus was always in a state of turmoil but according to President Binder, mud signaled progress.

The development was funded almost entirely from private donors such as Jessie Smith Dewar, whose foundation supported the expansions of Dewar Hall and the construction of Smith Hall.

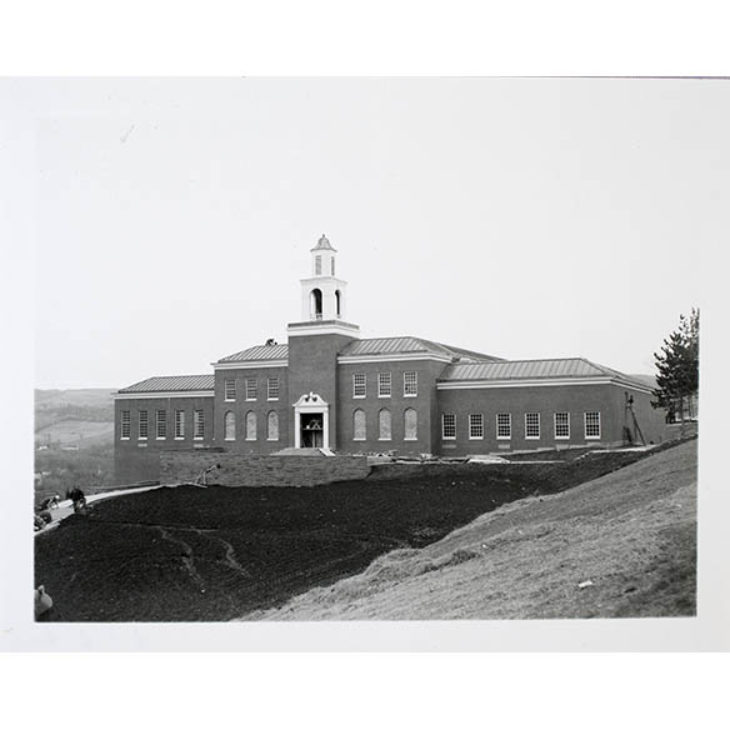

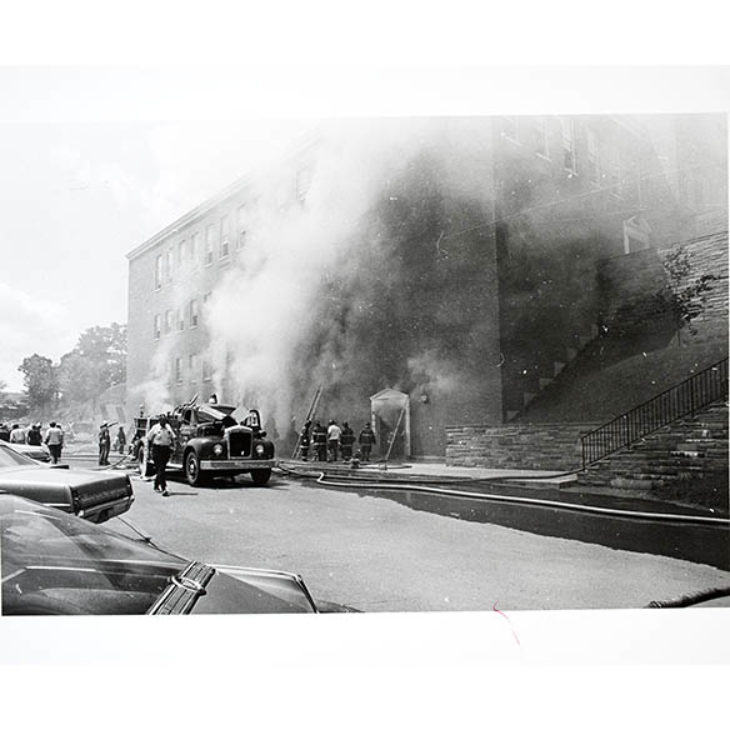

During this time the Yager building with a library and museum, and Binder Gymnasium, went up. Less than ten years after its construction, a fire raged through Yager damaging some of the Museum’s collections. Academic programs were expanded – during the sixties, Russian language and literature studies were added, and both Greek and Latin were brought back.

Campus Climate

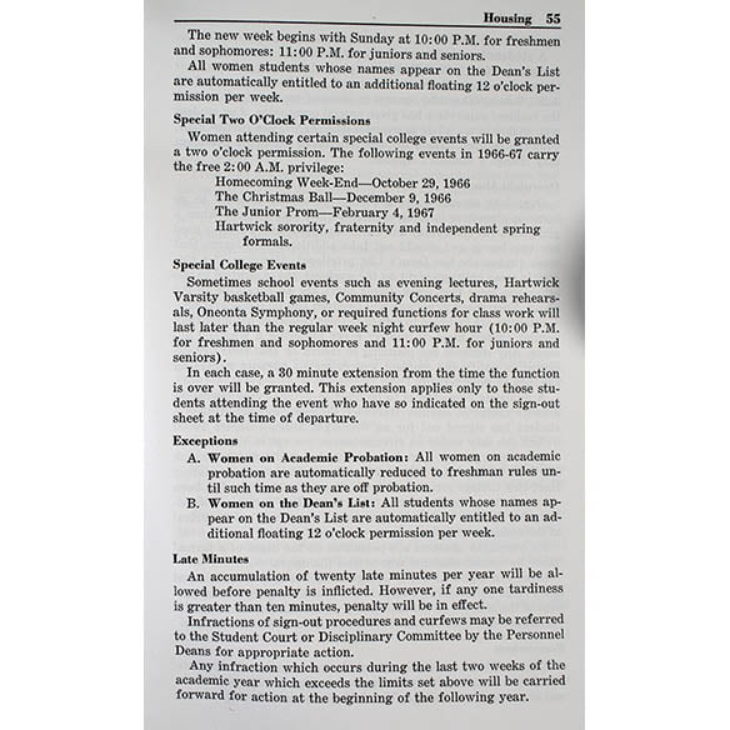

The campus climate was slow to reflect the rebellious times occurring throughout the nation but by the mid-1960s students were protesting college rules they considered outdated, including dress codes and curfews that impacted female students disparately. In 1968 Hartwick formally and amicably parted ways with the Lutheran Church, due to financial considerations. The break enabled Hartwick to begin receiving State subsidies for independent unaffiliated colleges and had the added benefit of bringing in trustees from a greater variety of backgrounds, and no longer just those with connections to Lutheranism.

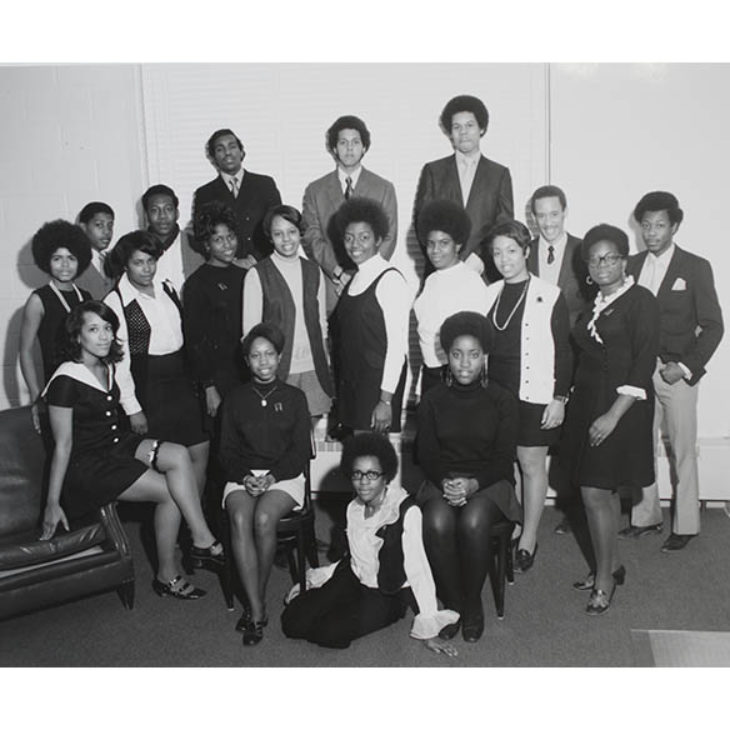

In 1969, the Student Senate approved the constitution of the Black Cultural Society, the first student organization dedicated to fostering awareness of Black history, culture and contributions. By the end of the decade enrollment was at 1,550 and the College assets had tripled.

Broadening Political and Social Concerns Represented

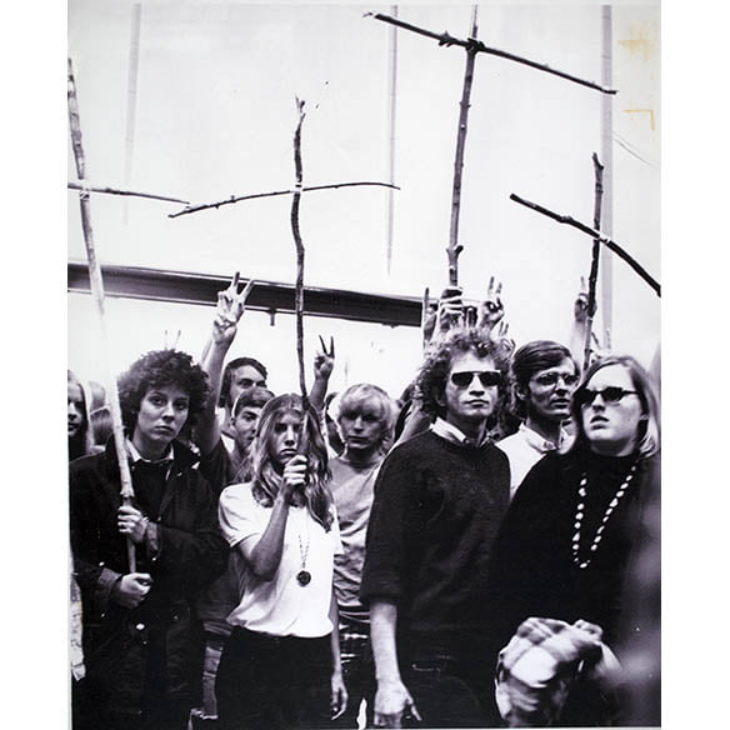

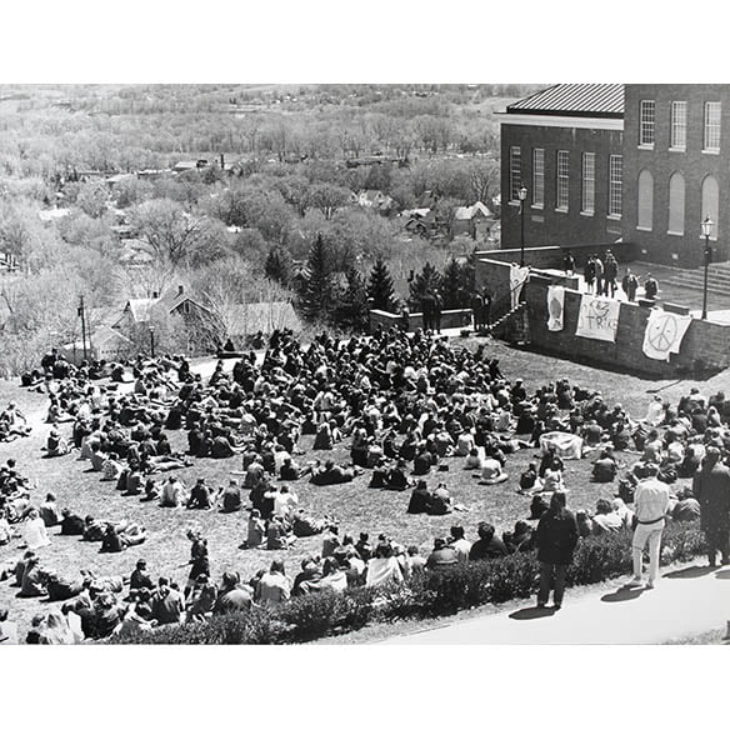

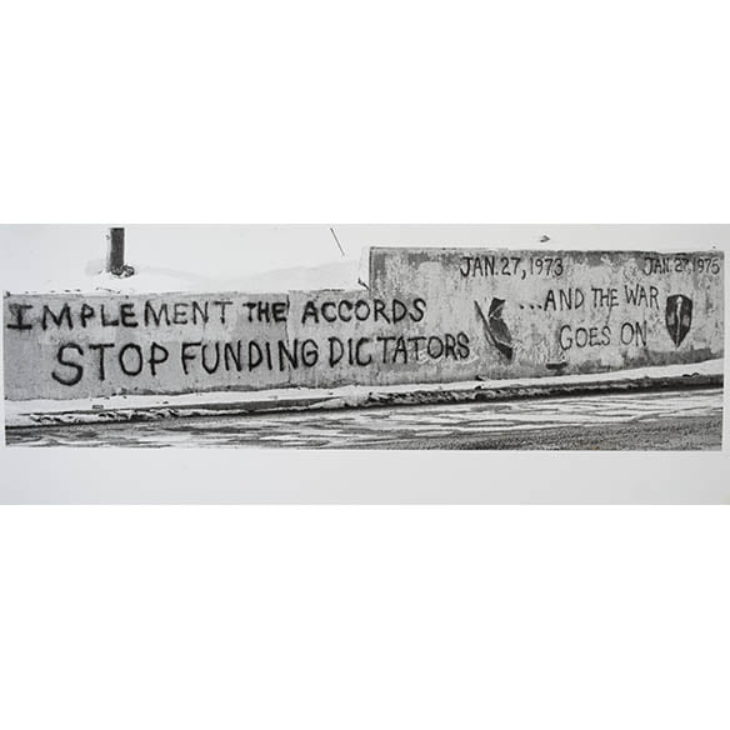

During the end of the 1960s and early 1970s Hartwick students and faculty were active in protesting US involvement in Vietnam, staging peaceful demonstrations and participating in the moratorium to end the war. Hartwick also became more diverse, with the Black Cultural Society evolving into the Society of Third-World Alliance to Implement Change (STATIC) and Ethnic Coalition both reflecting the broadening political and social concerns represented on campus.

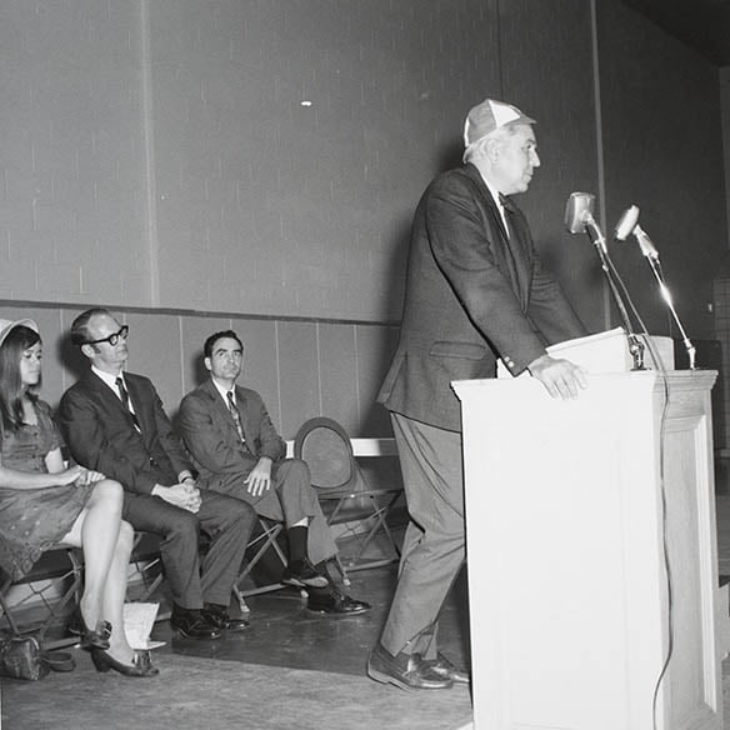

In 1969 Adolf G. Anderson had become Hartwick’s sixth president, bringing new approaches to a liberal arts and sciences education while urging students and faculty to “think in utopian terms.” During the 1970s, study-abroad programs were expanded with a greater emphasis placed on internships and off-campus experiences.

The 1971 acquisition of Pine Lake brought an additional 914 acres to the campus. Pine Lake, formerly a Catskills summer resort, became an environmental center that functioned as a laboratory for hands-on research and skill-building, a residence for students wanting to live near nature, and a place of recreation and reflection for the Hartwick community.

In 1973 a distinctive new Center for the Arts building, later renamed for President and Mrs. Anderson, was completed.

President Philip S. Wilder Jr.

During Anderson’s tenure enrollment peaked at 1,700, but it had begun to wane again and, coupled with large deficits in the late 70s, a decision was made to reduce faculty and staff numbers. A new president, Philip S. Wilder Jr., arrived in 1977, the year that the men’s soccer team won the NCAA Division I championship. Nevertheless, morale among employees was low with some predicting that Hartwick would not survive the recent setbacks. President Wilder, known as “Uncle Phil” to the students, strengthened the faculty and implemented strict cost-saving measures that produced a budget surplus by the start of the next decade. The 1980s at Hartwick were notable in part for a rekindling of interest in the College and Seminary histories, including a successful campaign to roll back the institution’s official founding date from 1928 to 1797.

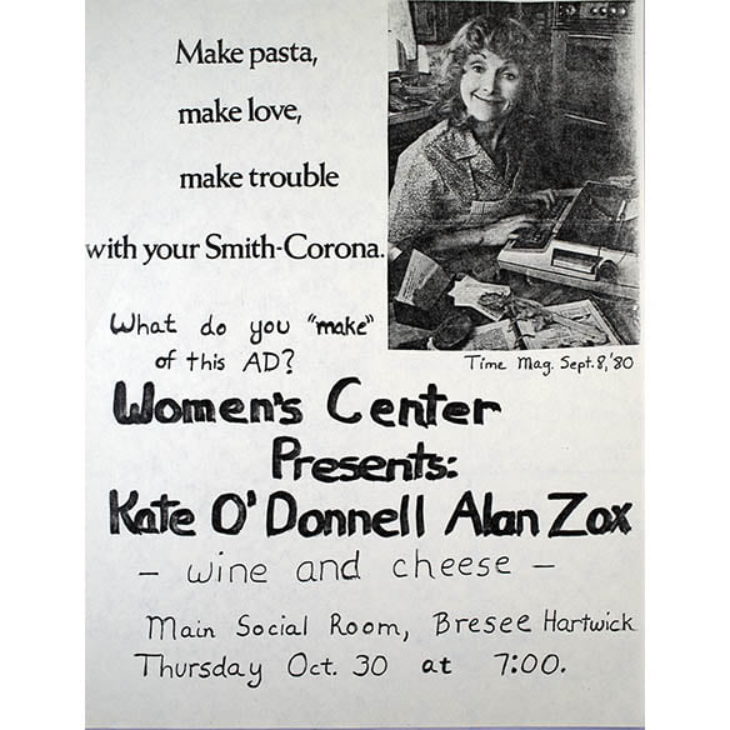

The Women’s Center, started in 1979, gained momentum in the eighties, mirroring the general growth of feminism on college campuses. Curricular changes meant new course requirements and educational experiences, with new majors added including accounting, biochemistry, computer science, information science and management. As the College moved toward the 1990s finances improved dramatically, with the endowment increasing from about $10 million to more than $50 million. This was due in great measure to the largest bequest ever received at Hartwick, given by its old friend Judge Abraham L. Kellogg, as well as an ambitious campaign undertaken in 1989 to raise $21 million. This period saw further growth of the physical plant, with the construction of the Perrella Health Center and Clark Hall, as well as the emergence of the January Term, or “J-term,” now a distinctive feature of Hartwick education with its study abroad options.

J Term, Diversity & 9/11

In 2000, Hartwick was recognized by the Chronicle of Higher Education for the number of students who studied abroad. Hartwick’s emphasis on experiential, international learning has remained strong throughout the last two decades, including January Terms (Known as J Terms) in destinations such as South Africa, Ireland, Spain, Australia, Bahamas, China, Czech Republic and Thailand.

Also in 2000, a Society of Sisters United (SOSU) chapter was founded at Hartwick to support young women of color, with a Brothers United group joining them four years later. With an emphasis on community service, SOSU/BU organized toy drives and volunteered at food banks.

In 2003, the Board of Trustees approved the College’s first statement on diversity. During this time, Hartwick instituted a more selective admissions process to improve the educational quality at the College. Hartwick joined colleges and universities in increasing student financial aid, granting almost five times the amount awarded at public institutions.

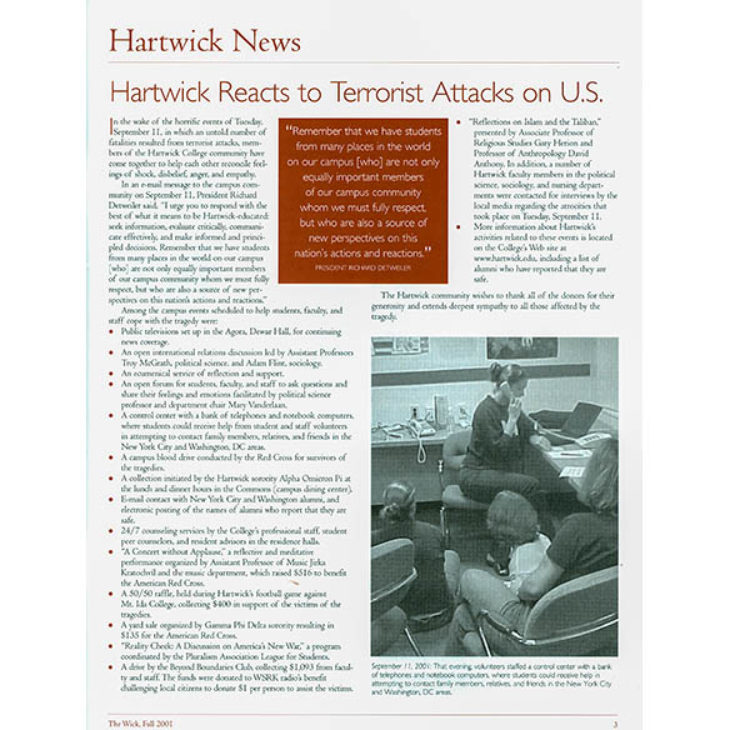

2001 brought the September 11 tragedy and its aftermath, which drew the campus community together in various ways. On the first anniversary of the attack, Hartwick held a vigil and memorial exhibit in the Yager Museum, and a forum on terrorism. In 2011 Hartwick was selected to host “New York Remembers” — one of 30 official exhibits in the state to commemorate the 10th anniversary of 9/11. Tributes to 2 Hartwick alumni who died on that day were presented.

President Richard P. Miller, Jr.

After serving for 11 years, President Detweiler announced his retirement in 2003, and in September, Richard P. Miller, Jr. became president. Miller emphasized community building and focused on re- establishing a solid financial base. During his five-year tenure, he helped the College build on its academic strengths by adopting a new curriculum that emphasized experiential learning.

In 2004, the now-annual Student Showcase was launched, celebrating the student-faculty collaborative scholarship that is a hallmark of a Hartwick education.

Hartwick student organizations, activities and traditions have changed, shaped by the variety of interests brought to campus with each incoming class. Hartwick began partnering with SUNY Oneonta in 2005 to produce OH-Fest, a free concert and carnival in downtown Oneonta intended to enhance the relationships between the two colleges and the City.

President Margaret L. Drugovich

Hartwick’s first female, and longest-serving, president took office in 2008. Dr. Margaret L. Drugovich arrived during a period of economic turmoil and began working on long-term financial and campus planning, including making Hartwick more affordable and diversifying its revenue streams.

Also, in 2008, the Cyrus B. Mehri Global Fellowship was established to enhance Hartwick’s commitment to global pluralism and to foster a diverse community. In 2009, Hartwick began offering three-year degree programs in 25 areas of study, as well as an 18-month nursing program.

Acknowledgements

This exhibit was made possible in part through research conducted by Ronald Bailey for his book "Hartwick College: A Bicentennial History 1797-1997."